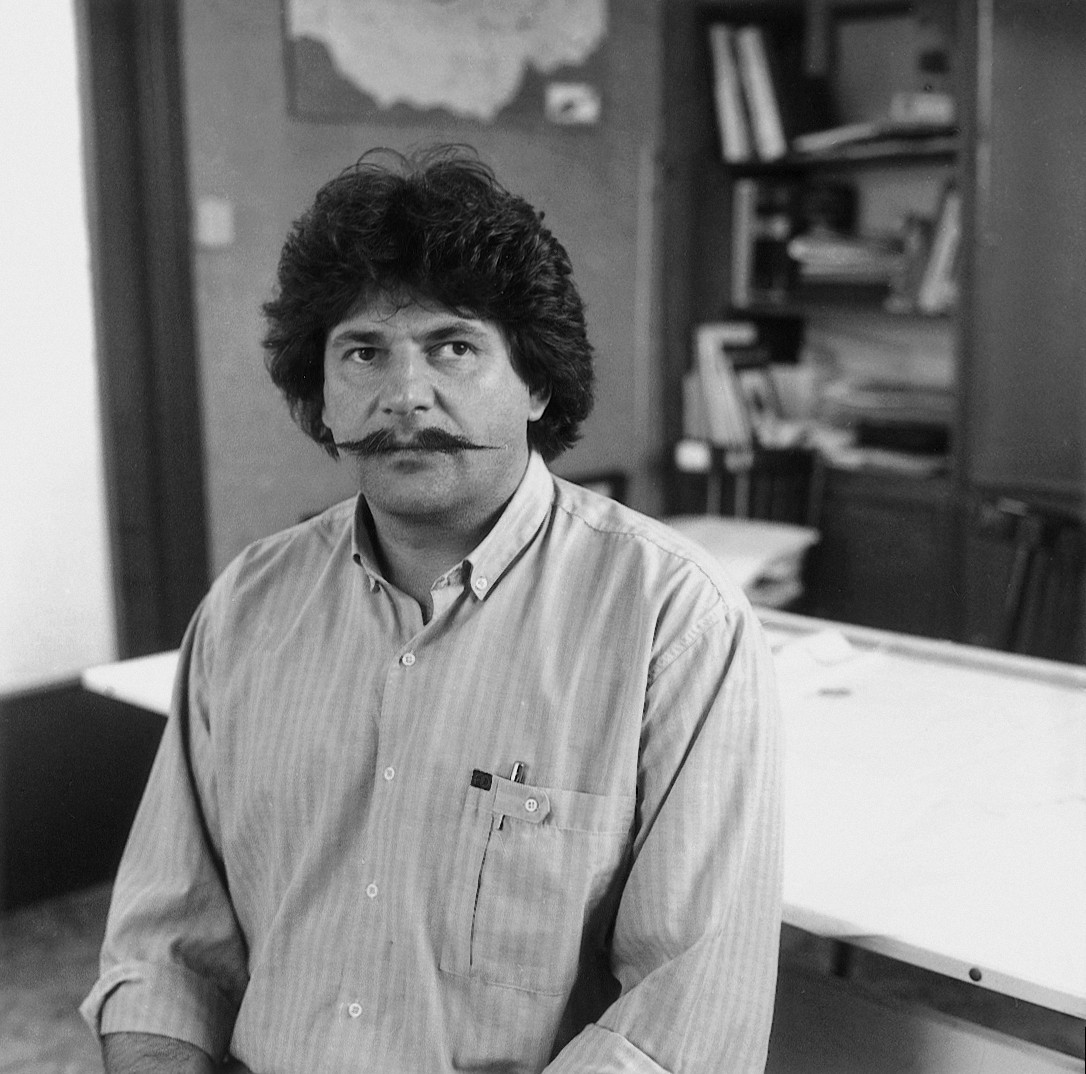

‘Artist of the Nation' Award winning architect and Regular Member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts Sándor Dévényi's name sounds familiar to all of us. Not so long ago two of the buildings of his design – the Gate of Gerecse Visitor Centre, situated near the Tatabánya-based (Hungary) statue of Hungary's mythological bird, and a pavilion in the village of Görcsöny – opened their gates. And recently, an exhibition showcasing his and Péter Pásztor's works opened in the Slovakia-based Kosice. Pesti Vigadó interviewed architect Sándor Dévényi about his career, organic architecture and his lifework exhibition staged in Pesti Vigadó from 1st February 2019.

Your name is frequently mentioned in the media in connection with your designs and exhibitions. How did this successful career begin?

I have always wanted to become an architect. In fact, I never had any other plans as far as my career was concerned. The reason for this might be that my bank clerk father, who built ship models and produced furniture as part of his creative activities, took his idea very seriously to raise and educate me to become an architect. He had acquaintances on the other side of the Iron Curtain and he asked them to send me Swiss architectural magazines, which portrayed architectural designs very different from the ones in contemporary Hungary. Another interesting personal detail is that I grew up in a house designed by Hungarian architect Alfréd Forbát. This building, constructed in 1937 in line with the Bauhaus tradition, seemed very progressive in the pitiful Hungarian reality of the 1950s: it was a house with sash windows and built-in wardrobes, and it had quite a modern floor plan. All in all, this built environment has had a fundamental impact on my whole life and career. In fact, I was really determined to apply to the Budapest Technical University and to pursue my career as an architect, which actually also means that my life course is very boring: I have been interested exclusively in construction and design. During my life, I have been doing what I have always liked.

In what ways were the Swiss buildings you saw in those professional journals different from contemporary Hungarian constructions?

For me, the main discovery did not lie so much in the novelty offered by these buildings, as I grew up in a modern house, but in the difference between contemporary Hungary and Western Europe: these journals visibly showed the difference between the dictatorship characterising Hungary in the 1950s and 1960s and the freedom enjoyed by Western Europe. In Hungary, there were no private constructions commissioned by individual people: everything was controlled by the state. And the freedom of Switzerland functioned like a shine of hope for me. In Switzerland, the most important element of architecture is regionalism, and modernity surfaces as an integral part of Swiss traditions. When we examine the world history of arts, we can see that arts always change and spirally grow, sometimes yielding common great styles, which then define the directions of arts. But when these directions wear out, arts fall to diverse pieces surfacing as regional styles, which then anew contribute to a novel consensus, resulting in a new global style. We can conclude that in the 20th century these styles succeed one another at increasingly rapid speeds, thereby they get increasingly intertwined, which causes a more chaotic scenario, in which context regional styles gain increasing importance. Hungarian organic architecture, which displays characteristic Hungarian elements and is known after designs by Hungarian architects György Csete and Imre Makovecz, is also such a regional style and this style was successful enough to be incorporated in the current global trend. The fact that this style was capable of contributing to the actual global trend clearly shows the value and impact of Hungarian organic architecture.

Is it possible to furnish a definition of Hungarian organic architecture? Does it have any recurrent unique elements and motives?

Important features of Hungarian organic architecture include its regional character, which means that is relies on and uses local traditions, it searches for its roots and it incorporates ages-old elements of Hungarian folk architecture. Frigyes Feszl, the designer who planned Pesti Vigadó's building, where my exhibition is to be showcased, was already trying to establish a specific Hungarian architectural form in his age. For this, he used elements of Hungarian ornamental folk art as well as elements from oriental, Indian, Iranian and Persian arts, with the latter group signalling the eastern origin of the Hungarian people. After Frigyes Feszl, Hungarian architects Ödön Lechner, Károly Koós and István Medgyaszay went the furthest in this quest for a unique Hungarian style: their tradition was picked up and followed by Imre Makovecz in the 2nd half of the 20th century. However, at that time – in an era characterised by the construction of high-rise buildings and state-owned big companies, when all architects were warned of the limits of their artistic fantasy – Makovecz's artistic choice was unmatched and revolutionary, and given this it was no wonder that Imre Makovecz was deliberately marginalised in his profession.

Many of today's newly-built constructions in Hungary are designed in line with the perspectives formulated by Hungarian organic architecture. Given this situation, could we now say that there has been a change in the design of buildings in Hungary?

Everything is constantly undergoing changes. The typical shapes advocated by organic architecture have slightly gone out of fashion by now: today's preferred art form in architecture is minimal art with its extremely simplified forms. In my view, the task of architecture is to serve and contribute to people's happiness. We humans live here on Earth in order to find happiness, and one means of finding happiness is to live in environments that make people happy. Obviously, a very limited environment with its restricted set of architectural means does have its own effect on people's happiness. Certainly, organic architecture has its own right of existence even today as we humans cannot detach ourselves from our environments. The best example of this is environmentally-conscious architecture, which imported many of the perspectives of organic architecture into its way of thinking. For example, it adopted one of the basic tenets of organic architecture: namely, that humans should try to live in a way that they should avoid destroying their environments. Today this constitutes a political goal already; the world has adopted many perspectives from the worldview of organic architecture, which signals that this architecture has several reasons to be proud of itself. It is also notable that organic architecture is not a style: it is rather a way of thinking, a philosophy boasting of its own unique forms, which forms fundamentally originate from floral and faunal forms thereby signalling man's proximity to nature and the observation of nature.

With respect to human's co-existence with the environment, can it be claimed that it is impossible, in line with the principles advocated by organic architecture, to design a building without knowing the exact location of the future building?

Yes, it is a basic tenet that the building should be connected to its environment, it be linked to it both in place and time. Since the very beginning of human existence, all places with a human population have had their own history and identity. The design of a building should be executed so that the form, proportion and mass of the building as well as the materials used for the construction of the building should befit the place in question. Integral development of the place should also include and extend to the building itself: the building should not be an eyesore, it should not hinder further development and it should not destroy its environment.

In acknowledgement of your career and lifework, you were awarded with the ‘Artist of the Nation' Award in 2017, which was founded by the Hungarian Parliament in an attempt to express the nation's "appreciation and esteem to those widely-recognised representatives of Hungarian art life who exhibit outstanding achievements". What does this "feedback", which realised in this Award, mean to you?

It is a great honour to have received this award, for which I am very grateful. The award perhaps signals that everything that I have created during the past 50 years of my career means something precious to the Hungarian community. It means that I may have contributed with something to the life of my fellow Hungarians, which contributions of mine may have made their lives slightly easier and happier.

You celebrated your 70th birthday in November. On this occasion, you showcased a joint exhibition with Péter Pásztor in the Slovakia-based Kosice; and another exhibition displaying your lifework will open in Pesti Vigadó in February. What exhibits are showcased at these exhibitions?

In commemoration of my friendship with Péter Pásztor, the small-scale chamber exhibition in Kosice presents posters listing and displaying our architectural design works of the past few years. Befitting the spirit of the place and the available floor space at Pesti Vigadó as well as the nature of lifework exhibitions, the showcasing in Pesti Vigadó allows for a more complex presentation of my designs. This exhibition presents what I have designed so far: not only designs that have been constructed so far but also some designs that have not yet realised. In addition, this event also signals some kind of "caesura" on the occasion of my birthday.

In the case of architects, the most important result of their work is the building itself. Nonetheless, the building cannot be transported to the site of the exhibition, thus the only means of presenting the general public with such architectural designs and end-products is by way of displaying some relevant plans and photos. To what extent does this allow for presenting an architect's lifework?

Architecture is not a genre for exhibition spaces. And so far I have not received any commission to design a building just because I have showcased an exhibition. If architects organise an exhibition of this kind, then they do so because they have a dream and vision in mind: they would like to teach and educate. I teach at the Hungary-based University of Pécs and I believe that if one has thoughts that other people can use, then they should be ready to share those thoughts with others.

EXHIBITION BY ARCHITECT SÁNDOR DÉVÉNYI

01/02/2019-24/03/2019