Interview with Regular Member, Member of the Board and Chair of the Committee of Education, Training and Science of the Hungarian Academy of Arts sculptor Ádám Farkas about his career and family legacy as well as about his statues erected at public places and his ‘Artist of the Nation' Award. Interview by Árpád Lesti.

Árpád Lesti: As far your parents, your father is book publisher Ferenc Farkas and your mother is graphic artist and book illustrator Anna Győrffy. What effects did the fact that you were lucky to have made acquaintances with renowned representatives of Hungarian art life already at an early age have on your childhood?

Ádám Farkas: In my case, childhood experiences are very influential but not in a direct way. My mother was a graphic artist, she designed illustrations for children's books and now the third generation is growing up using her books including the famous Hungarian collection of children's tales "Mosó Masa Mosodája (Laundry Racoon's Washroom)". In the morning, she used to sit down at her desk and drew all day, which to us seemed a perfectly normal thing to do. My father was friends with contemporary Hungarian literary figures and artists including Béni Ferenczi and his wife Erzsike, Gyula Illyés and his family, Lőrinc Szabó, László Németh, Aurél Bernáth, Jenő Barcsay; and sometimes even painter Béla Czóbel visited us. In other words, meeting members and representatives of the highest circles of Hungarian art life came naturally for us. At that time, I was certainly unaware of what all this meant. As a child, I was interested only in trees, plants, the nearby streamside and animals, so I enjoyed being close to nature. At home, I lived in a world where the natural environment (i.e. our huge garden where, fortunately and thanks to God, I have been living throughout my whole life) and the obvious presence of arts had a joint effect on me.

Árpád Lesti: It is commonly known that the Hungarian town of Szentendre assumes a distinguished role in Hungary's art life. With respect to your career, has it been decisive and relevant that so many artists lived and have been living in the town? And if so, to what extent?

Ádám Farkas: As compared today, this was felt much more intensively in my childhood and youth. Partly because the town was much smaller then. On the other hand, when I was a child, there were artists everywhere in the town. When you were walking, you could most certainly see some busy artists in the city: they were painting using their easels or were carrying folders full of their drawings. About 60 to 80 fine artists lived here, including Hungarian artists Dezső Korniss, Jenő Barcsay, Endre Bálint, Piroska Szántó, János Pirk, Pál Deim and towards the end of his life also Béla Kondor. The town was small enough for us to know one another: they could see my artwork and the majority of them reassuringly smiled at me from time to time, gave me professional advice and patted me on the shoulder in recognition of my work. As a rule, artists' careers are full of events of rising to fame, failure and fall. Mine, however, does not have these ups and downs: my career has been quite even. In fact, I attribute this to three motifs in my life: motivation by my family, the magnetic artistic power of Szentendre, and the natural environment. But even today I really enjoy doing physical work, which goes hand in hand with being the job of a sculptor.

Árpád Lesti: How would you characterise the life of a freshly graduated fine artist at the beginning of his career at the end of the 1960s?

Ádám Farkas: When I was a student at the Hungarian College of Fine Arts, I was clearly aware of what the institution was missing. So I consciously prepared myself to visit Paris and immerse myself in 20th century art in order to understand and directly experience those impulses that Paris still cherished at the end of the 1960s. For a time, I worked as a caretaker assistant: I got up very early in the morning, I cleaned each of the staircases of four houses, did the vacuuming, and did the rest of cleaning until 11 in the morning. Then I went to École Supérieure des Beaux-Arts to study as an unregistered student. After my classes, I left for the Louvre to study Greek and Roman sculpture as well as the Renaissance and Baroque ages. When all this experience matured in me, I started visiting Musée d'art Modern (i.e. the Paris Museum of Modern Art), and I was luckily also present when The Centre Pompidou opened. I was also fortunate enough to have had an insight into the Centre's operation, and this way I also had first-hand experience with a contemporary art centre. What I went through and learnt there eventually all surfaced in my art, and even if I got very attractive invitations to work in Paris and USA, I followed my original plans and idea to return home after having spent a year in France and professionally developed myself. In part, I was drawn home by our house and garden in Szentendre, and at that time I even had a studio there to work in. On the other hand, I was also determined and attracted by the idea that I was to bring home whatever I could professionally experience and learn in Paris. I also attribute this way of thinking to my family's disposition.

Árpád Lesti: Your statues erected at public places are as high as 10-12 metres, are visible from the far distance and are in fact monumental artworks that function as symbols. At the same time, you have also created statues for display in exhibition rooms, which perfectly rule the space. How does an artist choose whether he wants to create a monumental artwork or a smaller-scale work of art to be shown in an exhibition room?

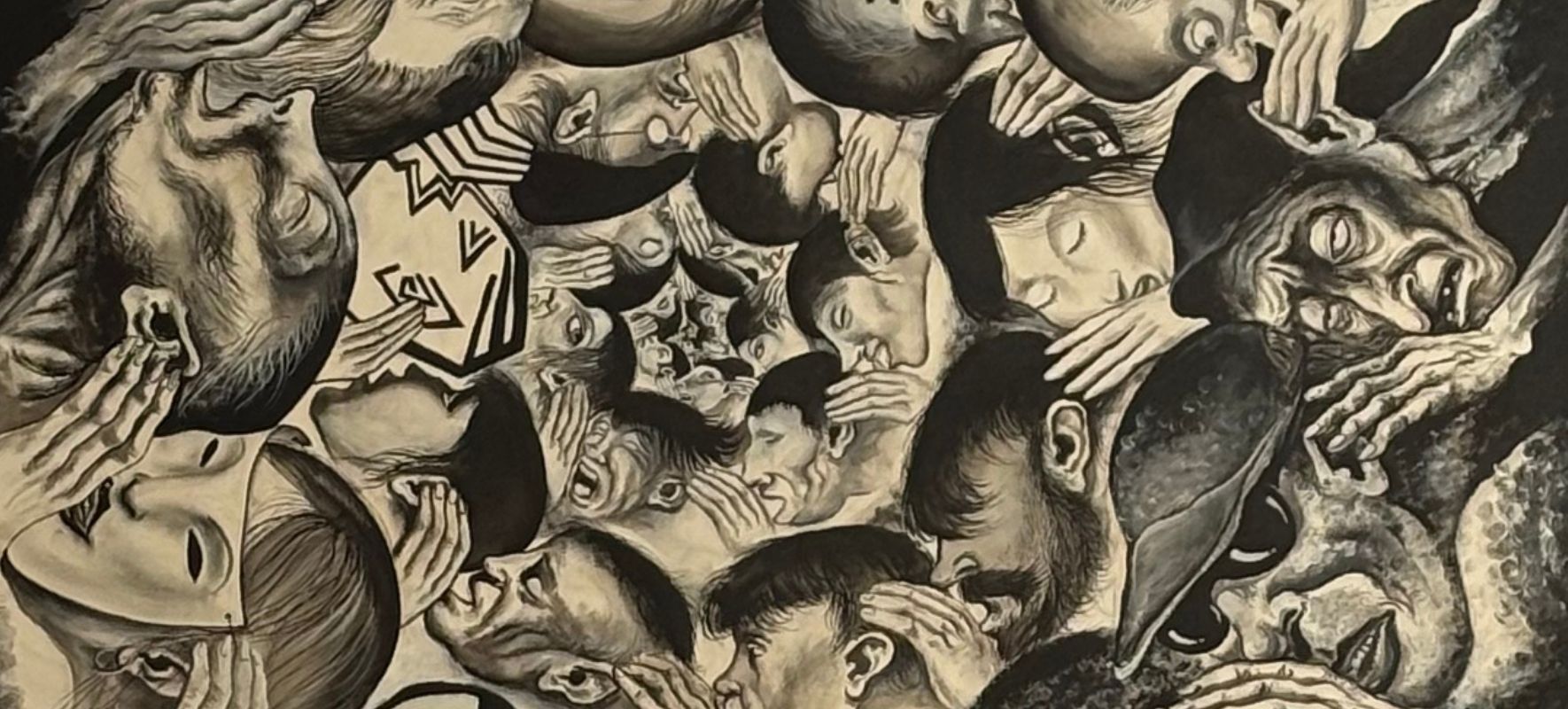

Ádám Farkas: The very statue appears only as a seed in one's mind. This initial idea is influenced by diverse compositional elements and effects, which may well be impacted by earlier works. Ultimately, all these accumulate and this way the final idea is born. Then this final idea gets created in the form of a sketch on paper. The drawing is not really the point. The focal issue is the process that goes from my brain through my hands straight to the drawing on the paper, which yields the formulation of the very thought. This is because the act of formulation and "voicing" reinforces this thought and notion. In art, "voicing" in fact means the very act of forming the thought in question. This is exactly the way the life of a statue starts: it may live on only as a thought but it may also be formulated eventually in different versions. If one has the time, they start working on an idea. Then they may prepare the idea in bigger and bigger sizes so that they can come up with further details and show the resulting work in its physical shape. Exhibitions are actually about presenting the idea in a physical shape. Some artists do not make do with this. They want their artworks to interact with a physical space, a square or a park in the town or in nature, and they do their best to make sure that the artwork thus amplified and reinforced communicates with people. I also had the desire to do and achieve something like this. I soon developed a method to accomplish this: when I was invited to take part at a call for applications concerning a future statue, I went to the given place. I walked in the neighbourhood and returned again and again to the place where the statue in question was to be erected until I could formulate a thought encapsulating the form to be created concerning the given space. These were the applications that I finally managed to win. As part of the preparation of such statues, almost all sculptors create intermediate versions that already feature at exhibitions or are ready to be displayed at such events. This is because during the creation and formation process several varieties are born: all one has to do is cast the smaller ones from bronze or sculpt them from wood or stone.

Árpád Lesti: You are Member of the Board and Chair of the Committee of Education, Training and Science of the Hungarian Academy of Arts. What motivates you to fill in these positions?

Ádám Farkas: For the past 8 years, I have continuously been working to foster and improve education through art at schools and to incorporate daily arts lessons in the curricula. The importance of having physical education lessons on a daily basis is now widely recognised and accepted. But the incorporation of daily arts lessons in the curricula would be just as important. Brain researchers fully agree with this idea: their studies confirm that experiential learning makes the retrieval of information one receives this way 10 times more likely and successful. Our goal is to put this fact, which is corroborated by scientific findings, into practice. If difficult classes come up in rapid succession during the mornings of each school day, children are unlikely to be able to pay attention during each class for 45 minutes: they get tired and become fed up with everything they are supposed to learn. In these situations, a singing, dancing or drawing class would be a great idea: during these lessons children would be engaged in playful activities, in the scope of which they could freely create either alone or in groups. Probably now it is time to make this idea come true as both the President of the Hungarian Academy of Arts conductor György Vashegyi and President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences neurobiologist Tamás Freund are very committed to this issue.

Árpád Lesti: To commemorate the 30th anniversary of the 1989-1990 change of regime in Hungary, academicians of the Hungarian Academy of Arts staged an exhibition entitled "The Passing of Time" to be showcased in Pesti Vigadó from February. Which of your artworks are you going to exhibit in the scope of this show?

Ádám Farkas: My artwork entitled "Angled Moebius" will be displayed. This a shell statue: it has the surface of a statue but it is hollow in the inside. It is constituted of a Moebius strip: its outer, light-reflecting surface twists and turns towards the inner space, and then it turns further and returns into itself. In these turns, the right angle refraction of planes and strip-like twists are concurrently present. This is the way I refer to the change of regime: it was not a revolution but rather a change without a refraction or sudden twist. It was in fact a turn in a different direction but was also a return to itself, a back turn. All in all, the objectives of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 were eventually realised 33 years later.

Árpád Lesti: In 2020, you received the ‘Artist of the Nation' Award. What does this award mean to you?

Ádám Farkas: Awards serve as feedback and confirmation. I have never desired to be recognised by awards, but each time I received one, I got justification that I was doing something well and I should go on and continue my efforts. On the day following the conferral of the award, I was very happy to receive congratulatory phone calls sitting in my armchair, but on the next day I was already out working in my studio. In essence, I think each person has a mission to complete: I have been offered such opportunities and support from my forbears, from my community and from my nation that can only be thanked for through my activities and work. I have been very extensively rewarded as compared to what I myself have given back so far, and as a consequence I still have a lot more to give back to the community. People, including me, seldom dare to say this out loud – and it is true to even those who know what true happiness is – that work provides pleasure. And work does give pleasure to me. Perhaps, there are shorter or longer periods when things just do not work out and I cannot solve some problem. But it is not really mere struggle when something does not work out: in that case, I restart everything because this is the path I feel I have walk. And I do go along my way as far as it takes me.