Pesti Vigadó interviewed Krisztina Kókay about her celebratory exhibition entitled '75 – Miracles of Lines and also asked about her artistic career spanning over a period of more than four decades.

How did your artistic career start?

I First of all, I am very grateful to my family. When I was around 8 years old, it became obvious that I was good at drawing: seeing this, my parents and grandparents supported and helped me in every way they could. Even if we were going through hard times financially, they bought me all the necessary equipment so that I could draw and paint.

In the Esztergom-based (Hungary) elementary school I attended, there was no teacher of drawing: it was either the physical education teacher or the singing and music teacher who taught us drawing, so there was no formal drawing education. To the school, one had to go along the Danube Embankment: the path was lined by plane trees on each side with the sight of the Eszergom Basilica above this view – this is a panorama all painters depict. Following this tradition, Hungarian painter Ágost Bajor often painted this scene: I took pleasure in watching him mix his paints. Then I asked my parents to buy me small tubes of oil paint. My family joined hands: my father and my grandfather bought paints and a lot of other things, my uncle prepared a box for the paints. I was about 12 or 13 years old when I sat down on the Danube Embankment and started painting. I did not realise I was being watched by a smaller crowd around me – all I did was paint.

In 1956, while the Hungarian Revolution was in its throes, one could hear the shots from a distance – all I did even then was paint on the Danube Embankment: I was depicting the Esztergom Basilica from the Calvary Hill. As a conclusion of my work so far, I took with me six oil paintings for presentation at my entrance exam to the Budapest-based Secondary School and Boarding School of Fine and Applied Arts.

In 1956, while the Hungarian Revolution was in its throes, one could hear the shots from a distance – all I did even then was paint on the Danube Embankment: I was depicting the Esztergom Basilica from the Calvary Hill. As a conclusion of my work so far, I took with me six oil paintings for presentation at my entrance exam to the Budapest-based Secondary School and Boarding School of Fine and Applied Arts.

At the Hungarian College of Fine Arts, where I continued my studies, we received quite a lot of drawing instruction and the teachers were very demanding when came to class work and especially drawing, which, in this field of art, constitutes the basis of everything: in painting an eye for proportions and a good artistic taste are very important. For us, drawing was like the alphabet for anyone who reads: one cannot live and create without it.

At the College I majored in textile art. Why did you choose to major in textile?

At that time, one could apply to colleges and universities after having completed a 1-year-long work placement in the scope of which they performed physical work. I and my fellow students were looking for a place where we could work with paints and we finally got placements in a textile factory, which promised to give us a small sum of student grant on condition we came back to the factory to take up jobs after having completed our studies of higher education. At the factory we were asked to perform exclusively copying tasks and our textile designs were not used, so we eventually smuggled our designs out of the factory in paper rolls, as if we were stealing something that was not originally ours.

Which do you consider your most memorable work?

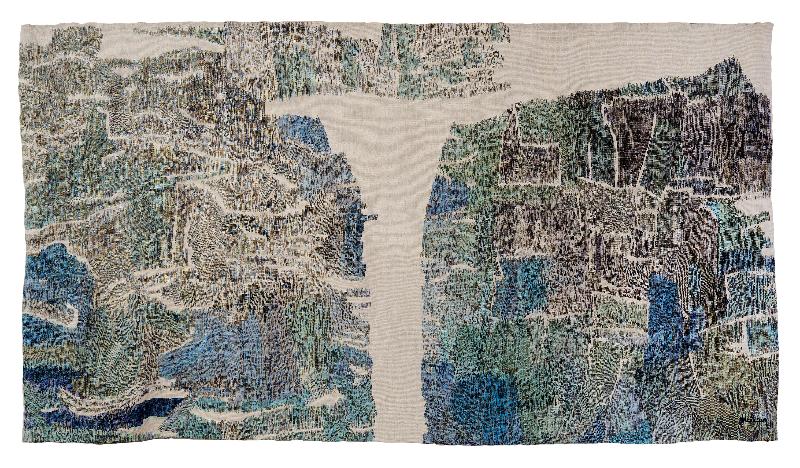

After graduating, I married, gave birth to my children and was a home-maker for the next 10 years. I was afraid that after such a long time I would not be able to continue my work. It was an incredibly fortunate event that one of my fellow students at the college, interior designer Villő Detre, who was commissioned to design the interior spaces of the hotel that is now called Hotel Flamenco, asked me to prepare 13 artworks with the dimensions of 7 metre in length and 1.7 metre in height to be installed in the hotel's hall and restaurant.

I was doing a lot of drawing while raising my kids, and it was a real miracle and lucky incident that one of my drawings inspired by a grapefruit was almost ready, and it befitted the hotel as far as its form and mood were concerned; all I had to do was design further variations of this drawing.

So I bought large wooden panels and stretched the textile over them. Then I placed the panels against the wall of the condominium where we lived and at night I projected the images I had previously designed over the textiles and I copied my graphic designs on these textiles. I worked until the early hours and I was almost ready when it eventually started snowing. In 1984 Villő Detre and I were awarded Nívó Prize for our work.

After a while, a new hotel manager took over at the hotel and he had a new idea and concept for the interior design of the hotel: the furniture was replaced and I was told to repaint my work or else it would be removed. Then, for a year I did nothing but crouch on a rolling scaffold and coloured my work as requested: and all this happened while the hotel guests were using the hall and restaurant as if there was no work going on.

Your 1997 exhibition staged in Vigadó Gallery was opened by Hungarian writer Magda Szabó. What memories have you got of this event?

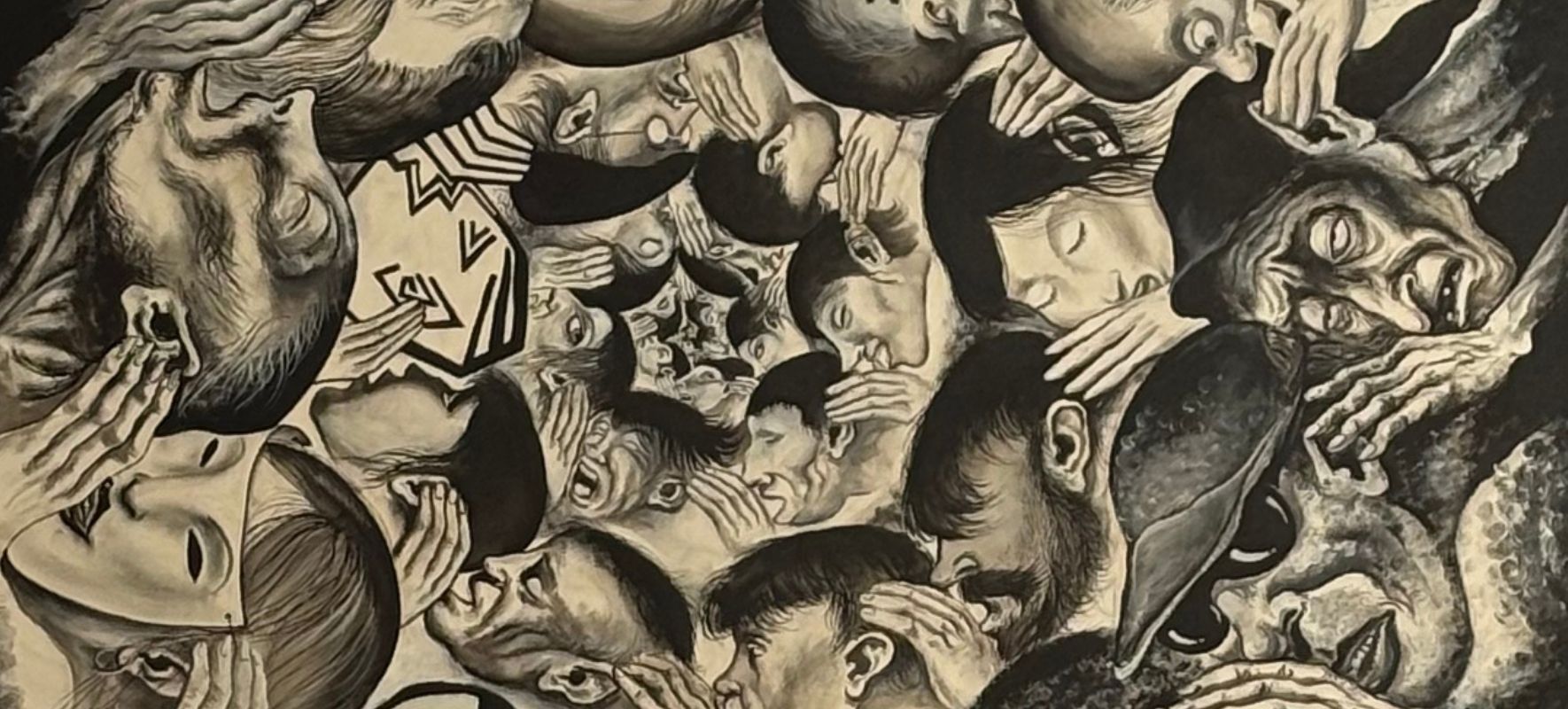

She gave a fantastic opening speech and I would like to take the opportunity to quote from it here: "Only the work of art is eternal, and it is only the path signalled by the artist that can help [the audience]. ... [in the scope of this exhibition] the artist unknowingly makes a confession, she speaks the unspeakable to the Lord Almighty, to the father of her art, to the world and to everybody. And our artist communicates all this with the help of her system of graphic composition consisting of tiny thin lines... All of her images are confessions. Yes, all of her images are confessions: through her works, a psychiatrist is trying to get to know herself, who is lost among the tiny thin lines. She is looking for an explanation of the identity of her creatures, she is looking for an explanation to explain her own self, and she is the first person to panic when she finally realises how much she could grasp of the ungraspable, how much she could draw of the unspeakable – working with a saint bird on her shoulder, under the pressure of the great responsibility art actually entails.

What is the main artistic concept behind the exhibition entitled '75 – Miracles of Lines?

For the purpose of the exhibition, our plan was to use the opportunities afforded by the available space at the location: it is very seldom that one can use so much space and such a huge wall surface for presenting their work. Here my large-scale works are displayed in a perfect spatial arrangement: I wanted to present the two cloaks of my design in the scope of one single exhibition. Unfortunately, for certain reasons, I could not have my monumental and very powerful textile work entitled Enclosed in Myself showcased in the scope of this exhibition but a graphic design of this work is on display "in compensation". I believe it is important not only for the general public but also for artists to sometimes see their works displayed at one exhibition: this is very illuminating.

On display at this exhibition are some floral studies dating back to 1976-78. These are strikingly fine artworks but, on the other hand, they are quite out-of-place among the sacrally-inspired images also shown here.

I drew there studies at the end of my collage years. These drawings are also interesting as they depict dried plants withered and tortured by life. These images depict the beauty of a dried plant or a tulip. Similarly to this, when we grow old, we also start to bear the signs of age after so many years of living. I found it intriguing how extensively and differently one can portray a small dried-up tulip petal and how much such an image can express.

Could you also tell us about the history of the two cloaks on display at this exhibition?

My drawing entitled The Cloaks was also on display in Fészek Gallery in 2015. Originally this was a small-scale graphic image, which I first enlarged and then drew lines around them, thereby creating letters out of the images. One of the cloaks bears the text of Admonitions by King Saint Stephen of Hungary, the other cloak has the Old-Hungarian poem Lamentations of Mary as the first piece on it, then it continues with Hungarian poems from Zsuzsanna Erdélyi's collection entitled Folk Prayers and it ends with poems by Hungarian poets Bálint Balassi and Sándor Márai, with the poem entitled Angel from Heaven as the very last piece. So that this last poem was also fully included, I started to write the poem on the cloak from the end backwards taking care that the allocated space for it was also observed: ultimately the lines met.

I instinctively draw my lines on the paper I use: thereby my art reveals emotions, opinions, dramatic events and joy, which I cannot or do not want to express using words.

***

KRISZTINA KÓKAY '75 - MIRACLES OF LINES

1/12/2019-27/01/2019

Pesti Vigadó | VI. Exhibition Hall