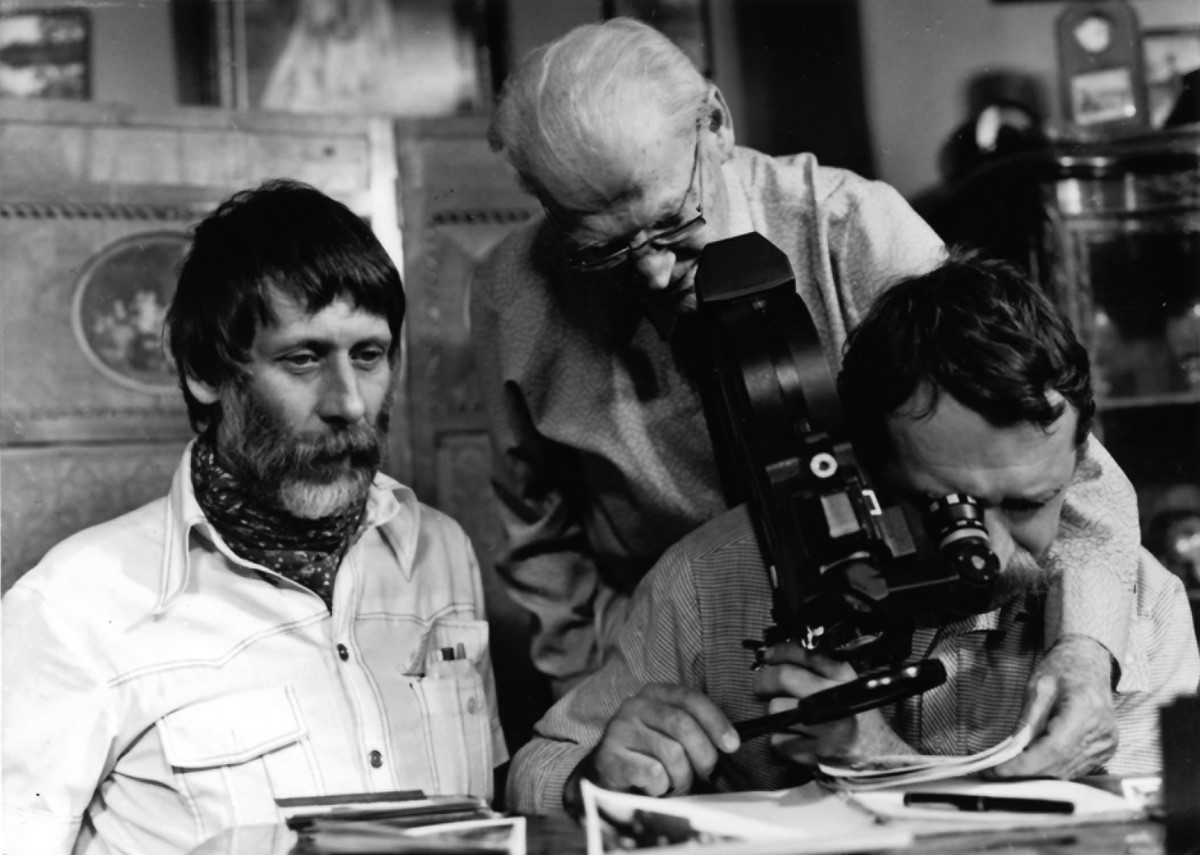

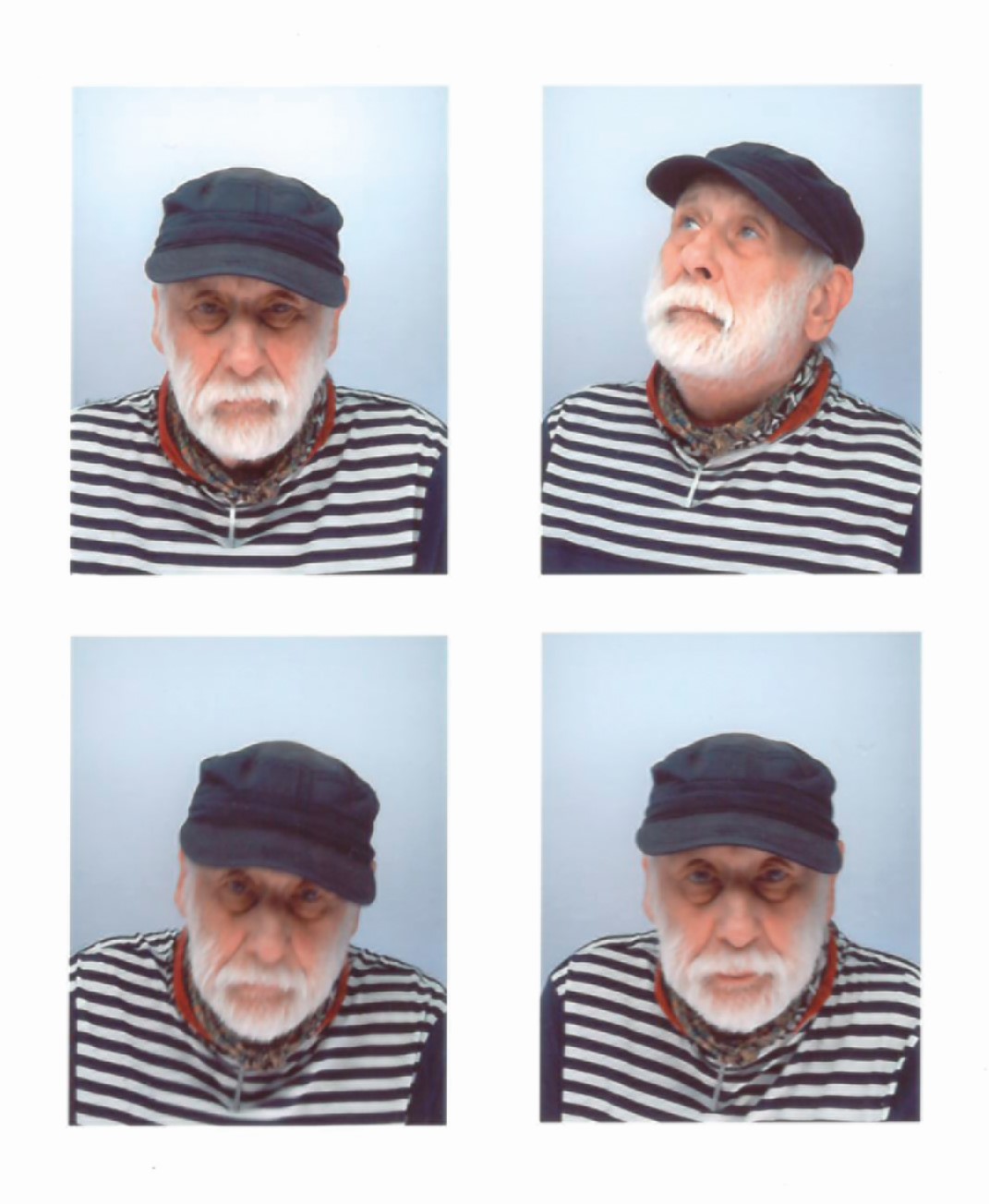

Balázs Béla and Kossuth Awards winning film director and Full Member of the Hungarian Academy of Arts István Dárday is celebrating his 80th birthday this year. Pesti Vigadó interviewed him about Hungary's Balázs Béla Studio, the main concept behind document–feature films (docufiction) as well as about non-professional actors and actresses in his films. Interview by Árpád Lesti.

Your name has become closely associated with Balázs Béla Studio. What exactly was this Studio and why is this Studio important and decisive from a historical point of view?

During the political changes of the 1990s, censorship used to be an integral part of Hungary's cultural life: all films produced were to be pre-screened and if there was something in these films that offended political interests, this triggered a severe censorship-purpose discussion and process about the elimination of those parts of the film in question that were considered insulting to those holding political power. As opposed to this, films produced in Balázs Béla Studio, from the very beginning of the establishment of the Studio, were not required to be pre-screened and there was no verbal political dictatorship concerning any aspect of the films produced there. At the same time, this workshop-like Studio was completely free to use the monetary funds allocated to it for each year, and the five-member management committee, in agreement with the members of the Studio, decided on which of the synopses, film plans and screenplays to realise. At that time, this was a great thing for film professionals as well as also for the rest of the entire artistic world in Hungary (as films include music, literature and visual arts). On Gábor Body's initiation, Balázs Béla Studio mobilised musicians, fine artists, linguists and avant-garde artists to take part in the artistic and professional life of the Studio.

Why was the then political power motivated to guarantee so much autonomy?

It was a non-public and non-communicated but very serious intention on the part of the party elite to establish a quarantine this way. Through this, they wanted to create a confined space where people could be observed: what capabilities people possessed, what ideas they had and what their worldviews were like. At that time, nobody knew about the communist regime's security intelligence agency: we only suspected that there were people among us who reported on us but we were clearly unaware of how far the security intelligence agency could reach, how big and extensive their organisation was, and how effective and goal-conscious they were. In fact, professionals in Balázs Béla Studio, including myself, enjoyed full artistic freedom, on the one hand, but we were under full control, on the other hand, as artists' professional courses and endeavours were completely visible to the communist regime's leaders of cultural politics. This provided the regime with information about who to trust and who to give a green light to concerning their work, and who to restrict as they were not fully supportive of the then ruling regime.

How did you relate to and manage this situation?

Professionals belonging to our age group, especially that group of artists who were engaged in producing the film series entitled "Public Education Series" felt it was our calling to continue working with the openness and artistic freedom we enjoyed in Balázs Béla Studio even after our five-year-long membership in the Studio had expired and we had found ourselves working independently in our fields of expertise. Several generations before us were committed to the same goal, but it was only our generation that could realise this in practice in 1980. This act of ours generated opposition and hostilities. In 1980, we established the so-called "fifth studio" under the name Társulás Stúdió, which offered the prospects of reaping the benefits formerly associated with Balázs Béla Studio and offered further opportunities in numerous respects. These benefits included going even more open and transparent as far the general public and professional circles were concerned, finding more flexible artistic and production opportunities, and renewing cinematic arts.

At that time, the motion picture industry in Hungary was very much divided due to a number of reasons. Out of these reasons, the most conflictual issue was an unsaid and non-communicated "agreement" that was concluded between the Hungarian art world (including the world of cinematic arts) and the Communist Party after the Hungarian Revolution and Freedom Fight of 1956. This agreement was about observing and respecting each other's points of views and refraining from generating or intensifying already existing conflicts. The communist Kádár regime viewed the film industry as a very important means of communication: contemporary films projected the image that Hungary was enjoying great freedom. For that reason, a film director was a very influential person in Hungary: those who could achieve a higher position and authority during their careers also became influential abroad. And for that reason, it was important for the regime what kind of image this person and their films would communicate about Hungary in foreign countries.

Actually, by way of setting up Társulás Studio, Hungarian party person Imre Pozsgay wanted to create a more practicable and humanistic concept of public education in the face of György Aczél one of the most influential figures of Hungarian cultural politics and one of the leaders of the Communist Party's Central Committee. The establishment of the Studio, in itself, foreshadowed that many of the film directors and members of the communist power elite were determined to regard Társulás Studio an enemy.

As members of a later generation, people of my age group were not involved in the above-mentioned "agreement". Many of us did not even know about it. We believed that truth and reality must be portrayed and that contemporary reality must used for changing life. Because of this perspective, many of us undertook to enter conflicts and disagreements in order to protect the film we were about to create. I prepared the majority of my films in cooperation with Györgyi Szalay, and in our case – and I am not exaggerating now – almost all of our feature films took about a year to go through censorship and be approved. For example, our film entitled "Jutalomutazás" (Bonus Trip) took ages to be screened in cinemas. I remember the last phase of the censorship process took place in Zánka, in the then country-wide centre for pioneers. All pioneer leaders were invited and we also had the head of the competent department at the Cultural Ministry's Film Directorate with us for the screening. The film was screened to this audience: the audience was having a whale of a time and were laughing throughout the whole film but one person at the end of the screening came up to us and asked if we were not afraid of them beating us to death...

Censorship did everything it could to prevent the film's public screening or to have some of the scenes removed from the film. But in party politics hierarchy pioneers did not have so much power so eventually, after a long-long time, the film was screened to the general public.

In addition to the above, it is worth noting that the development and popularity of documentarism and the creation of Társulás Studio were greatly facilitated by the fact that by the beginning of the 1970s traditional feature films had lost their potential to shed light on the essence of social conflicts in a very deep and realistic way. There were very powerful combinations of docufictions, so these films took over the former role of document films and positioned themselves in key positions, right in the centre of attention. Initially, these films were difficult to sell and screen. They were not so much welcome at film festivals, either. Yet, Társulás Studio could produce films that were acknowledged by Golden Camera awards at the Cannes Film Festival and by an Oscar nomination and were greatly esteemed at highly-acclaimed festival awards. This way the international film world could also see and acknowledge the renewal of the Hungarian film, which foreign critics termed "Budapest School".

In several of your films, you worked with non-professional actors and actresses. How did this idea emerge?

There were a few occasions in the history of film when non-professionals previously played roles in films, but at that time this became a strategic concept of our whole movement. Non-professionals are believed to more credibly present dramas, interconnections and contradictions pictured in the films. On the other hand, we did not believe it was a good idea if one actor appeared on the screen in different roles and assumed different characters in different films. Our concept was to portray real joyful events and real dramatic events of our real lives in our films. Non-professionals never became accomplished actors or actresses and they were never offered this opportunity, either. At the very start, they were told that if they got the role and if they felt like it, we would be making the given film together, but afterwards their lives were to return to their normal courses.

How did you find the actors and actresses?

In the case of the film entitled "Bonus Trip", we had the same method of finding the characters. At that time, we toured Hungary and screened a pre-selected short film. We travelled to a smaller town or a village, invited local party secretaries to the screening and we started talking to them about the topic introduced in the film. We did not tell them that we were looking for amateur actors and actresses. During the discussion, we could see who shared a perspective compatible with our artistic concept and we could also see who was behaving freely and casually in front of the camera. We had around ten screening events at diverse places and at each place we selected one or two people, then we got to know them quite thoroughly and we prepared real test shots with them. Afterwards we selected the most suitable persons.

It is very important to know and bear in mind that the people appearing in the scenes were never instructed jointly, so they did not know in advance what their partners were going to say. This contributes to documentary films' realistic way of presentation and increased credibility.

The most important feature of the entire Budapest School was that it was based on a very powerful and conscious directorial and artistic concept. Technically speaking, this was slightly improvisational but, on the other hand, the placement and movement of the two cameras were carried out very carefully in a well-designed way. And the actors and actresses got used to working with no cameras, lamps or any other filming technology around them while the film was shot.

Many believe that the essence of the genre of docufiction lies in that this genre does not work with professional but with lay actors and actresses.

I think this is a serious misunderstanding. By exploring difficult-to-see interconnections in the context of our everyday lives and by eliminating any sense of purposeful composition in films, docufiction builds on realistic and unexpected plots throughout the entire film, and in the viewer the film creates a feeling of being personally present in the plot. Documentarist films create the following feeling in their beholders: viewers keep pondering about the events and conflicts pictured while seemingly taking part in the scenes themselves as if they were experiencing their own lives. These screenings also offer the creation of a different, non-traditional way of reception as far as the quality and nature of the reception itself is concerned, and this, from the point of view of experiencing the work of art, is an important aspect.

Thanks to the director's very carefully structured philosophy subtly appearing on the screen, the plot very closely presents people with their acts characterised by spontaneous eventuality and the characters are entangled in a fight with their rationally guided emotions. The viewer is forced to live side by side with these people in a relationship characterised by love or hatred, because these people, in the company of the viewers, are experiencing one-off and non-recurring events in their lives.

What kind of feedback did you receive from the actors and actresses?

Feedback was diverse but in the majority of cases they were happy to star in a film and were fully aware of what the film was about. In fact, a central strategic point of the artistic functioning and operation of our entire movement is the film series entitled "Public Education Series". This is a five-part classical documentary series, which was prepared in Hungary's Heves and Borsod Counties for a year, and the actual filming took another year in the same counties.

We lived among the people portrayed in the series. We lived in workers' hostels... The relationship we had with the people filmed did not resemble the usual relationships between the society and a film director. Finally, we selected a family for our film: the father and the mother were teachers, and all of the children except one were preparing to become teachers, too. This latter child wanted to continue his studies at a vocational school. The concept behind the film was to offer a realistic presentation of the educational system as far as professional, political and human resource related problems were concerned, and our goal was also to uncover the problems experienced by educators. The film wanted to depict that, at that time, teachers were forced to work in a system of lies, which surrounded their lives, and we also wanted to show that very political structure in which all this was happening. Based on several decades of feedback, we can honestly say that we were successful in doing so.

However, in the case of each document film a usual and typical moral responsibility on the part of the director surfaces: to what extent is the director allowed to explore the conflicts of an ordinary family? This is a great issue as even after the publication of the film this family will have to continue living their usual lives, and there are very few people who consent to having their "secrets" exposed to the general public. The film series entitled "Public Education Series" presented the life of this family. The dramatic discrepancies of the educational work of the teachers portrayed and revealed such great depths that were previously unbelievable for us, too.

The breadwinner Lajos Bulyáki understood this and realised that it was through their tragedy that we wanted to present the harsh problems of the entire educational system to the Hungarian public, because changes could be triggered only this way. Due to the complexity and the analysis of the issue on table presented in the film, only very-very few people would have consented to the publication of such a movie featuring their families. Contrary to all this and contrary to the fact that everybody knew the given family in the town where they lived, the family assuming the leading roles in the film decided that their personal interests were of secondary importance as compared to public interests. They assumed it was more important for the general public to see what the situation in the educational system was like, and they did not mind having a few "inconvenient" and embarrassing experiences with relatives and acquaintances concerning the events pictured in the film.

During the filming, which took over a year, we, the film-makers and the family members became real friends. But this decision of the family's was more than just a gesture of friendship: through their decision they became allies of a concept that aimed at renewing the Hungarian educational system.

In the end, the completed film was banned from public screening both in movies and in the television for several years... At the Miskolc Documentary Festival, the film-makers (namely, István Dárday, László Mihályffy; Ferenc Papp; Györgyi Szalai, László Vitézy and Pál Wilt) received an award in the long documentary category. However, contemporary cultural politics failed to bestow the highest award recognising exceptional acting talents on the father and thereby also failed to acknowledge this self-sacrificing undertaking by this breadwinning teacher.

If one has produced a film but if the film is not screened but is merely stored somewhere with no access for the general public, is the creator not afraid that the entire film will lose its topicality by the time the film gets released? Are creators not afraid that their films, after a long while, will no longer be capable of exerting their expected effects?

This danger is associated with each artwork. But if the artwork is deep enough and if it appropriately explores related psychological and societal connections and implications, then this danger is really minimal. Each year numerous documentaries and documentarist feature films are produces at all levels of the education system that would be suitable for teaching history at a desirable depth, extent and level. I believe this is so as no oral communication or history book is more capable of presenting the most vital human aspects or the most relevant aspects of public life in any historical period than the diverse range of cathartic experiences offered by moving images.